Jumping-Off Place Launch Celebration and Screening of American Socialist: The Life and Times of Eugene Debs, Sunday, May 5th at 4:00 at the Digital Gym

By AFT Guild Political Action VP Jim Miller

This coming Sunday, May 5th at 4 PM, the Jumping-Off Place will be hosting a mixer before the screening of Yale Strom’s film, American Socialist: The Life and Times of Eugene Victor Debs at the Digital Gym (1100 Market Street, downtown). The period this documentary covers was a centrally important moment for the American labor, the civil rights movements, and American democracy.

As Adam Hochschild writes in American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis, the history of the time between World War I and the 1920s tells the dark tale of “mass imprisonments, torture, vigilante violence, censorship, killings of Black Americans, and for more that is not marked by commemorative plagues, museum exhibits, or Ken Burns documentaries. It is a story of how a war supposedly fought to make the world safe for democracy became the excuse for a war against democracy at home.”

Learning about the significance of this history is key to a deeper understanding of the fundamental challenges that American democracy has always faced. Hochschild underscores this in his study when he observes that, “The toxic currents of racism, nativism, Red-baiting, and contempt for the rule of law have long flowed through American life.” We see this, he observes, “in McCarthyism, in the rocks thrown at Black children entering previously all-white schools, and in the demagoguery of politicians like Richard Nixon, George Wallace, and Donald Trump.” It’s as American as apple pie.

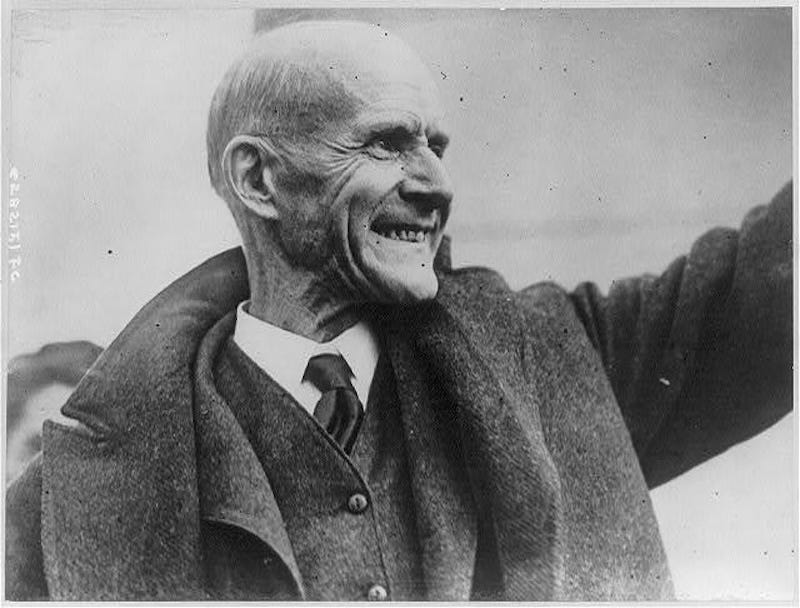

Eugene Debs was portrayed by his enemies as un-American and served a long jail term for his opposition to the United States’ involvement in World War I, when he gave speeches arguing that “men were fit for something better than slavery and cannon fodder.” Debs was also the man who, in 1892, organized the American Railway Union (ARU) that sought to organize all classes of railway men and do more for them than the more exclusive AFL Railroad Brotherhoods had done. In 1894, the ARU-led Pullman Strike involved 150,000 workers shutting down eleven lines. President Cleveland responded by calling in Federal troops and the courts came in with an injunction based on the Sherman Anti-Trust Act to help break the strike.

In the midst of this struggle, Samuel Gompers’ AFL offered too little help too late, and the General Strike collapsed. The American press blamed “anarchist” immigrants and portrayed labor unrest as the product of “foreign agitation” rather than legitimate grievance. Demonizing immigrants became a trusty stalking horse to help instill fear and distrust of the labor movement into the hearts of the public. For many, it worked. Nonetheless, despite the failure of this strike, it remains one of the most heroic struggles in American labor history and planted seeds that would later bloom.

Debs, himself, was both loathed by the powerful and loved by millions of other Americans, mostly working folks. He was, Hochschild writes, “Saintly, gentle, and charismatic . . . a faithful Christian and the fervor he inspired in his followers was almost religious.” His Socialists “commanded considerable support and could not be condemned as violent revolutionaries for they competed at the polls.”

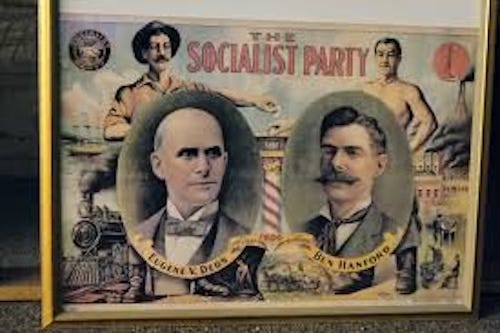

The Socialist Party that emerged during this period called for an electoral struggle to build a new societal order based on public ownership of industry and a thoroughgoing democracy that would include labor reforms, social security, as well as safety and health reforms. It was composed of Knights of Labor veterans, old populists, German and Russian immigrants, and other progressives. Debs, its leader, ran for President multiple times—once from jail. By 1912, more than 2,000 Socialists held public offices across the United States, making the Socialist Party a significant electoral force and a potential threat to the two major American parties dominated by capital.

Eventually, in the wake of a barrage of legal and extralegal repressions, mainstream progressives ended up stealing issues from the Socialists as things like banning child labor, regulating work hours, and instituting health and safety reforms—which all began as Socialist proposals—started to enter American law and politics after being co-opted by the mainstream parties.

Thus, it is an interesting question to ask whether the Socialist Party was a failure or a success and to ponder their legacy. In The Decline of Socialism in America 1912-1925, James Weinstein observes that:

Everyone recognizes the United States as the only industrialized nation in the world with no significant movement for socialism. Since World War II, most Americans have come to assume that this has always been so, for not only in the affluent post-war years but even during the Great Depression (when American capitalism had collapsed and could revive itself only with the start of arms production for another world war), the idea of socialism remained the property of small and isolated groups. The reasons for this are also well known. They include the high American standard of living, the impact of free land and unique class mobility in a society with no feudal past, and the speed and ease with which sophisticated liberals, starting with Theodore Roosevelt, have been able to appropriate enough of the left’s demands to capture a good part of a potential Socialist following. Then, too, the United States, being an immigrant nation, has been sharply divided along lines of race and national origin as along those of class. Suppression of leftists and of their right to speak, removal of Socialist organizations and prosecution of their leaders by federal, state, and local governments have also weakened the left.

Weinstein’s analysis here is clear-eyed but is lacking as a proper understanding of the profound impact of the full-scale repression of the left in the United States during the Progressive era, a deficiency that Hochschild’s work addresses. The repression of radicals was made easier by the fact that the American Labor Movement was split on World War I, with many on the left, like Tom Mooney, Emma Goldman, and others, opposing it, while, by 1917 Gompers and the AFL supported the war.

What this meant was that during the first Red Scare, much of the American working class was split, leaving opponents of the war more isolated. Reactionary forces in the government seized on this and the passages of the Espionage Act and the Sedition Act gave the government great power to censor newspapers, ban literature from the US mail, and jail dissenters. This was accompanied by giving a blind eye to extralegal violence against labor and civil rights activists, which resulted in mob violence, the lynching of labor leaders, Black Americans, and immigrants along with the systemic dismantling of fundamental democratic rights to free speech, public assembly, and freedom of thought, as even membership in a union like the IWW became a crime.

Hence, Eugene Debs went to jail for an anti-war speech, the radical Industrial Workers of the World were systematically persecuted, thousands of immigrants were unjustly deported, and deadly white riots shook the country, devastating Black communities. All the while repression continued with the Palmer raids arresting thousands of “aliens” and communists, and twenty-two states passed criminal syndicalism laws aimed at anyone advocating “illegal labor tactics.” Here in California, 164 IWW members went to jail.

And after all the repression of radicals had decimated their ranks, corporate America followed suit with new open shop drives against all unions. Hence, rather than appreciating AFL loyalty, business went after mainstream labor. This and a short depression hit unions hard resulting in the loss of a quarter of the membership of the AFL.

In the face of this wave of repression, Eugene Debs ran for President from his jail cell and got close to one million votes. The IWW never fully recovered from this period as a significant force in labor, though their legend remains and we forget the importance of this history at our peril.

Indeed, as Hochschild argues in the conclusion of American Midnight:

To keep these dark forces from overwhelming American society once again will require a lot from us. Knowledge of our history, for one thing, so we can better see the danger signals and the first drumbeats of demagoguery. Brave men and women both inside and outside the government, like those who spoke the truth and stuck to their principles more than one hundred years ago. A more equitable distribution of wealth, so that there will not be tens of millions of people economically losing ground and looking for scapegoats to blame. A mass media far less craven toward those in power than it was in 1917-21. And above all, a vigilant respect for civil rights and constitutional safeguards, to save ourselves from ever slipping back into the darkness again.

Thus, remembering the brutal history of American labor’s radical past is crucial is we hope to starve off the present darkness and build a better future for all of us.