By Justin Akers Chacón, AFT Local 1931

Over the last two years, public school teachers across the country have gone on strike, held mass, statewide rallies, coordinated “sick-outs”, and taken a variety of other actions to confront and reverse the attacks on working and learning conditions in public education. In both “red” and “blue” states, and even in charter schools, teachers’ unions have fought for and won higher wages, better working conditions, and other concessions for their themselves, their students, and their communities.

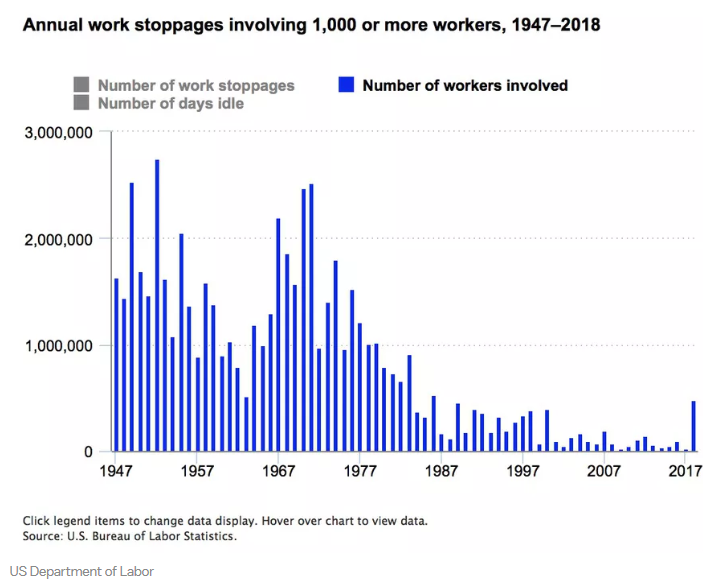

While strike levels have consistently plummeted for decades, public school teachers are at the forefront of a revival of labor militancy and activism. As one report concluded, “nearly all of the 20 major work stoppages in 2018 involved massive labor strikes, which ended up boosting wages for thousands of workers. And public school teachers fueled a lot of the resistance.” The rise in teacher’s strikes has also played a role in inspiring an increase in strikes in some other sectors.

- Figure 1.

- Figure 2.

Attack on Teacher’s Unions and Public Education

Income and working conditions for teachers have been in steady decline for years, as state governments have systematically cut taxes, slashed education budgets, and froze or cut teacher salaries. A coordinated political effort to weaken and dismantle unions has been the main objective of an employer’s offensive that has been waged in the US for over the last four decades.

Over the last decade specifically, there has been an intensified campaign to discredit and dismantle public sector unions.

Union-busting is a pivotal strategy in the arena of class warfare, as labor organization represents the most potent and indomitable form of worker-based organization. As such, unions are the foremost obstacle to and bulwark against the unfettered accumulation of profit through increased exploitation.

In varying degrees and different junctures in history, unions have also played the role of advocate in defending or advancing the social and political interests of the working class as a whole. In recent years this has ranged from supporting amnesty for undocumented workers and their families, the living-wage movement, to fighting against sexual harassment in the workplace.

The increasing frequency and scale of assaults on unions in the last two decades one that has been occurring in the context of a larger political strategy referred to as “neoliberalism.” This framework explains how the intensification of one-sided, top-down class war is occurring as a mechanism to increase “profitability” at a time of prolonged economic crisis and instability. It is further necessitated by increasing global competition from rising economic rivals, primarily China.

The aggregate rate of profit accumulated by the US corporate sector has been on a downward trajectory over the last several decades, further punctuated by significant recessions. One solution has been to “back-fill” declining income by other means. This has included cutting taxes for the rich, reducing social budgets, and generally reverse-engineering redistributive policies at all levels of government so that wealth flows from the bottom up instead of the other way around.

The policies are enacted at the federal electoral by representatives of the capitalist class, or members of this class who move directly into government. They further filter down through state and municipal government, are acted upon by appointees in state bureaucracies, and popularized by an army of paid ideologues in think tanks.

For these groups, neoliberalism has represented an instinctive impulse to restore their economic preeminence through the inward pursuit of new models of accumulation that look to the increased commoditization of the social and public sector. They have also turned to more aggressively attacking political obstacles to their ambitions.

The name harkens back to an earlier ‘economic liberalism’ when corporations and the super-wealthy directly controlled and ran the state in their own interests. This cherished past, from the point of view of the most self-conscious neoliberal, is perhaps best located before the passage of the Wagner Act in 1935, which began the process for legalizing labor unions.

The experience of teachers and their unions epitomizes the work of these policies. There have been numerous policy initiatives designed to hobble and weaken teacher’s unions and collective bargaining. These include efforts to eliminate tenure, restrict the use of membership dues for political purposes, scaling back pension, restricting their right to collectively bargain or strike, and many more. Furthermore, there have been extensive reductions in funding public education, including and the privatization of public institutions.

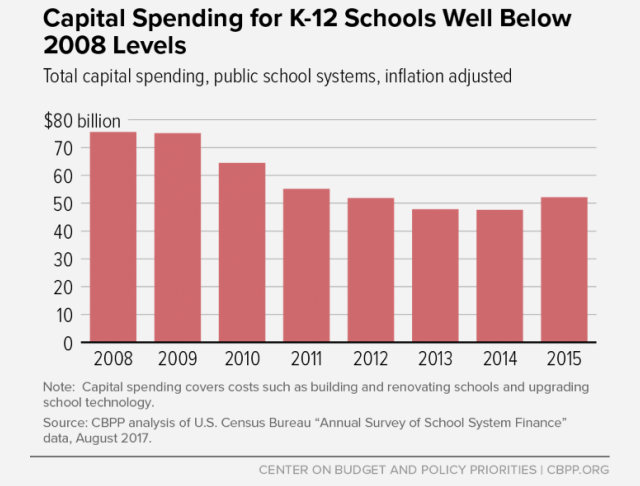

The defunding of public education has been a concerted project across many states over the last decade. As one recent study shows,

Public investment in K-12 schools — crucial for communities to thrive and the U.S. economy to offer broad opportunity — has declined dramatically in a number of states over the last decade. Worse, some of the deepest-cutting states have also cut income tax rates, weakening their main revenue source for supporting schools. States have not only failed to restore funding since the massive budget cuts enacted during the last economic recession (see figure 3), but some have continued to cut to the bone. States where teachers have been part of the new strike and protest movement, including North Carolina, Arizona, and Oklahoma, for instance, have enacted income tax cuts that cost tens or hundreds of millions of dollars each year since the recovery from the last recession a decade ago.

Figure 3.

The attack on unions has been even more pronounced in “right-to-work” states. This refers to (misnamed) anti-union legislative policies passed in some states that favor employers and weaken collective bargaining rights in the workplace. Along with other provisions that already prohibit teacher from going on strike in 38 states, right-to-work legislation prohibits the automatic inclusion of all workers in a union when a majority votes for in favor.

These policies allow employers to cultivate divisions that further financially weaken unions as they allow workers to opt out of paying dues – even as they enjoy the benefits of the contract. In some right-to-work states, such as Oklahoma, teacher’s pay fell over $6,000 below the cost of living, pushing many educators and their families into poverty in the years leading up to their strike and subsequent $6,000 annual wage gain.

In 2018, the anti-union right-to-work law went national after a rightwing majority in the Supreme court voted in favor of the so-called Janus decision. Nevertheless, the strikes and pro-union sentiment spreading among workers has limited its impact so far. According to data from the National Education Association (NEA), “constant pay for educators— meaning pay adjusted for the cost of living in each state as determined by the Consumer Price Index—in some states has decreased as much as 15 percent between the years 2000 through 2017.” Despite these attacks, teachers are fighting back, even in these right-to-work states and demonstrating a high level of unity and solidarity in the face of preponderant opposition.

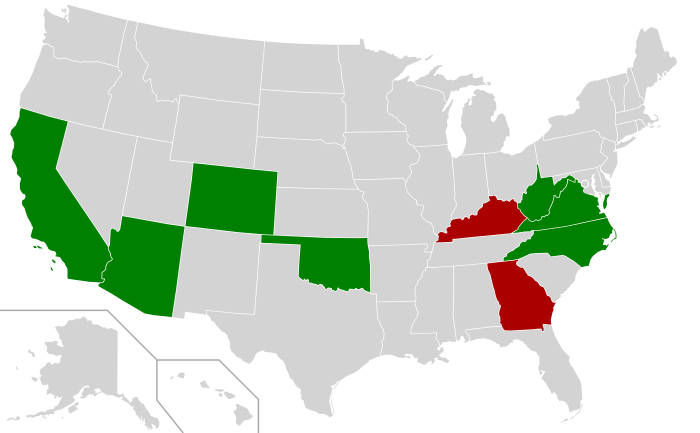

2018 to April 2019 saw 17 education strikes and major protests in 11 states.

Source: Wikipedia

Teachers Challenge Business Unionism

In some cases, a revitalized teacher’s movement has been initiated by the emergence of progressive caucuses challenging entrenched, conservative union leaderships that continue to adhere to the failed practice of “business” unionism.

Business unionism is a major contributing factor to the decline of organized labor, especially in the face of a coordinated capitalist class-orchestrated effort against them. This model posits that union affairs should be run strictly like a business, that owner-worker relationships and negotiations be treated as a mutually beneficial partnership, that union demands should focus exclusively on “bread-and-butter” issues, and that strikes be avoided at all costs.

Business unionism has a long history in the American Federation of Labor and gradually supplanted the more radical “class-struggle” unionism that gained a significant foothold in the CIO-led industrial unions that split from the AFL in 1936. Between 1937-1954, CIO unions grew rapidly. The class-struggle political current within the industrial labor movement had gained prominence as Socialists and Communist Party members played a central role in building up the ranks of CIO unions and affiliates. This occurred in conjunction with the rising militancy across the working class as a whole, which produced the greatest and most prolonged strike wave in US history during the Depression and post-war years (see Figure 1).

The class-struggle model treated the interests of employers and workers as class-based and therefore diametrically opposed and irreconcilable. Therefore, it is reasoned, only by striking could workers match the preponderant political power of the employers. The collective withholding of labor was the most effective, and in fact, the only real, negotiating implement potent enough to force concessions from recalcitrant employers. The CIO sought to organize the masses of unorganized industrial workers at that time, including millions of women, African-Americans, Mexicans, and other people of Color and immigrants excluded from the craft unions of the AFL. These so-called “skilled” unions had championed business unionism and were therefore favored by the employers over the CIO.

CIO unions leveraged the power of the new industrial working class and sought to not only uplift the wages, benefits, and working conditions for the millions of workers, but to also become a political force to radically democratize society. Foreshadowing what would later be referred to as “social unionism”, the CIO backed campaigns to challenge Jim Crow segregation, and other forms structural inequality that prevented the full development and integration of working class people.

As a result of a rising labor movement the CIO became a target for repression under the aegis of the Cold War. One of the principle aims of McCarthyism and the government-led, bipartisan “Red Scare” campaigns was to purge the substantial ranks of left-wing labor leadership and membership from the union movement and help facilitate its trajectory back towards business unionism with the reunification with the AFL in 1955.

Since then, we have seen the restoration of business unionism and subsequent decline of unionization as a whole. This has contributed to the erosion and erasure of hard-fought gains, the retreat from strikes and all forms of militancy, the acceptance of concessionary contracts, the disengagement of membership and their exclusion in day-to-day affairs and subsequent decline in membership, and the abandonment of community involvement and organizing and labor solidarity.

The end result was to restore business unionism as the dominant labor ideology, which was further normalized and entrenched as a defensive strategy as a new employer’s offensive was kicked off in the late 1970s as an effort to roll-back and wipe-out the unions altogether (see Figure 1 above).

The new teacher’s movement is being driven by “caucuses” that are forming within the existing unions to vie for leadership as existential crisis has become a reality. Caucus groups have formed in various unions in school districts around the country, from Chicago to Los Angeles, to Seattle, New York, Baltimore, and many more.

They are being led by a new generation of union militants and those with leftwing convictions to revive aspects of class-struggle and social unionism. In other cases, the push for change is coming from seemingly spontaneous insurgencies driven by rank and file membership, democratic and inclusive in nature, and using innovative and creative organizing techniques.

Rank and File members take the initiative

For many teachers, especially where union leadership has succumbed to the worst aspects of business union sclerosis, the rank and file have reclaimed their unions and pushed inert leaderships to take action. The erosion of wages, lethal slashes to pensions and health care, and the dramatic cuts in education funding overall that is having a detrimental impact on students and their performance have combined to push teachers into bold action.

When the leadership of the West Virginia Education Association backed down from taking action for a 5% wage increase in early 2018, the teachers took action on their own. They organized meet-ups, organized phone trees, and used social media to coordinate a strike. As the New York Times reported,

It was a crucial turning point, and a telling one. With no collective bargaining rights, no contract, and no legal right to strike, the teachers had managed to mount a statewide work stoppage anyway, and make their demands heard, marshal public support, and stick together until they won. And the rank and file, not union leaders, came to call the shots.

They maintained near absolute unity, garnered broad public support, and forced the state government to concede against virtually impossible legal odds. This model spread to other states where the union leadership remained stagnant. Mass mobilization of the membership from the bottom-up, has become a new model.

In Arizona, they used social media to organize when the official leadership would not. The union president of the Arizona Educators Association publicly refused to support calls for a strike and even discouraged protests in the state capital. The rank and file leaders across the state and formed their own Facebook group “Arizona Educators United.”

As one Arizona newspaper reported,

At 40,000 strong, Arizona Educators United pushed aside the Arizona Education Association, the political group typically charged with imposing their will at the Legislature. They’re showing the union and others how to organize. Arizona Educators United and the Red for Ed movement invited public education employees and their supporters to vent their frustrations publicly on Facebook. Within 24 hours, thousands had joined the conversation and many asked the same question: Will Arizona be the next to strike?

They did strike, and won a 20% wage increase.

Both models, reform caucuses and rank and file-led action, have begun to push unions into action and to re-define and re-position themselves in such a way as to lead and inspire other workers to follow suit across the country. Between 2018 and April of 2019, at least 17 strikes and mass rallies for workplace action have taken place across eleven states. Since April 2019, there have been at least 8 more teacher strikes and large rallies for workplace action across six states, and they show no sign of abating. In April, for instance, 90% teachers in Mississippi voted to either go on a sick-out, or authorize a statewide strike.

First and foremost, teachers are more willing to leverage their greatest strength: the ability to collectively withhold their labor power by going on strike. Through their unions, teachers are broadening their outlook to include demands that reflect the interests of their students and the overall communities in which they are situated. Lastly, they are engaging in on-the ground advocacy campaigns and political struggle, reviving the spirit of the progressive sectors of the CIO at its height of power and influence. They are standing in solidarity against injustice and supporting campaigns of social change that directly challenge conditions of social inequality that afflict the working class as a whole.

There’s Power in a Union – and Community Solidarity

Teachers unions have a positive multiplier effect on their communities, not only improving conditions for the teachers, but also benefiting students and communities as a whole.

According to recent studies there is correlation between union density, higher average teacher salaries, and higher student achievement. Where unions are stronger, there is more overall funding within the district. According to a study published in the Economics of Education Review, this translates to more funds going to pay. Furthermore, according to a recent MIT study, union-density led to higher funding levels, which in turn has also lead to increased student achievement overall.

Another recent Baylor study shows that the practice of unions to motivate their members to take political action within their communities tends to increase egalitarian patterns of political representation within those same communities.

Through the nexus between public school teachers and the working class communities they serve, more educators are recognizing the strategic importance of social unionism. This includes community base building through constant outreach and dialogue, recognition and incorporation of parent’s demands, and teacher-student solidarity. These create a bulwark of popular support.

This is crucial as city and state government administrations, especially those most virulently anti-union and neoliberal in orientation, rely on dividing and pitting the parents against the teachers and unions in order to prevent or weaken strikes.

The growing commitment to social unionism, for instance, helps explain the overwhelmingly high levels of student and parent solidarity and backing for the recent strikes—key to strike success—even as they disrupted daily life. During the strikes in Denver, Colorado and Oakland California, students organized walkouts, marches, and rallies in solidarity with their striking teachers.

In Oklahoma, striking teachers were assisted by parents and community members in organizing day-care centers for kids to go during the day while their parents worked. These acts of mutual solidarity have become a common features of the strikes. In Los Angeles, parent and community groups organized a “Tacos for Teachers” campaign to provide food to striking teachers. In Denver, it was “Tamales for Teachers.”

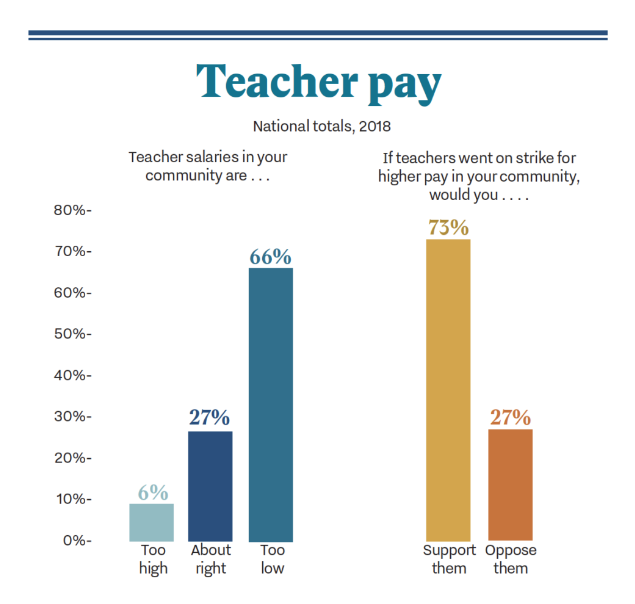

Source: Phi Delta Kappa (PDK) Poll, 2018

Social Unionism

As educators need community support to win gains in the workplace, so too do the learning conditions of their students and the well-being of their communities directly impact their work. This is especially the case for poor and working class communities, where perpetual cuts in social programs and services have significantly impacted access to basic resources. Schools and their staff have become an essential support hub for communities to have access to support services ranging from meals to health care to after-school programs.

Educators understand how poverty, euphemistically referred to as “food and shelter insecurity,” affect student learning. Budget cuts that impact their students also increase their workloads in multi-faceted ways.

Recognizing how the interests of teachers, students, and families interlock, unions have begun to include into their strike demands student-centered issues as well as social and political demands that impact the whole communities.

As a report in Education Week noted,

The flavor of the teacher strikes has changed. Unlike last year, when teachers across the country shared a similar narrative of crumbling classrooms and stagnant paychecks, the strike demands now are far-reaching. Now, teachers are pushing back against education-reform policies, like charter schools and performance-based pay. They’re also fighting for social-justice initiatives, like sanctuary protections for undocumented students.

The Chicago Teachers Union (CTU) paved the way for the social unionism approach in 2012, with a successful nine day strike under the slogan “The Schools Students Deserve.” In the years prior to the strike, the CTU invested heavily in building community relations. This included door-to-door outreach, teacher-parent meetings, and other public forums to forge common goals through dialogue between the union, teachers, students and their families.

The strike demands included smaller class sizes alongside the call for increased teacher compensation. Other demands linked carefully overlapped the issue of teacher pay and student performance, or reflected larger social goals. These included the demand for a curriculum of language, art, music, and physical education for all students, and for nursing and social-work services inside schools to address the needs of low-income students.

In the latest wave of strikes, student-centered and social demands were included across the board. In Arizona, the 2018 strike included the demand that the state restore nearly a $1 billion in funding to education that had been since 2008. The state government spent 14 percent less per pupil on school funding on the eve of the strike than it did than it did a decade prior, primarily through cutting corporate income taxes and personal income taxes cuts that primarily benefitted the richest. Meanwhile, teachers’ salaries decreased over 10% over the same period.

In effect, the teachers were now superseding the statehouse and legislature and using their strike to push the government to meet the needs of the majority directly. After a week-long walkout, the state government agreed to a $644 million restoration. As one report concluded, “through labor militancy, Arizona teachers succeeded in forcing Republicans to make investments in public education that they did not want to.”

In Los Angeles, the nation’s second-largest school district, teachers went out on their first strike in thirty years. The demands of their largely student-centered strike included: more librarians, counselors, nurses, and mental health professionals for their schools, smaller class sizes, reduced standardized testing, and a host of other gains.

In a district that is comprised of 73% Latino students, many come from migrant or mixed status families who face the impact or threat of arrest, detention, and deportation on a regular basis. ICE repression sews terror into the communities and traumatizes students. In recognition of this social injustice, and the way it impacts the learning environment, the union incorporated a demand that the schools provide an immigration attorney to help counsel students and their families.

The teacher’s picket lines stayed firm and were bolstered by a massive show of popular support and approval, leading the school board to concede after one week.

Model for a New Movement

We are in the midst of a teacher-led strike wave that is breaking out of the limits imposed by the failed model of business unionism and uprooting the legitimacy of neoliberal, class-war politics. This new militancy, powered by the rank and file, is challenging and replacing ineffective leadership, demonstrating a willingness to strike, and taking up social demands affecting whole communities as an act of working class unity and solidarity.

This strike movement and its trail of victories (so far) are at the forefront of resisting and overturning the dominant ideological dogma of the employer’s offensive and anti-union crusade institutionalized and normalized over the last four decades. These strikes show that: unions are not irrelevant and that strikes do work, that employers (whether private or public) are not too powerful to beat, that workers can wield power and influence that can match and surpass that of corporate money, and that widening inequality is something to fight against and not passively accept.

Teachers in other embattled sectors of the public education system—such as those in community and state colleges—can learn a lot from this new movement and take some pages from their playbook.

0 Comments